“Nobody Died At Sandy Hook”

Chapter Two

By “Dr. Eowyn” aka Maria Hsia Chang

“Infowars reporter Dan Bidondi said (5:45 mark), “The school’s been closed down for God knows how long. [Neighbors] can’t understand why there were kids in that building because it was condemned.” pg. 30

Dan Bidondi—a never-was professional wrestler turned “reporter” for Alex Jones—doesn’t bother to name a single one of these supposed “neighbors.” Not one. Meanwhile, interviews with actual local residents are widely available, and they show the opposite: no confusion whatsoever about Sandy Hook Elementary being open and occupied by students. If the school had truly been closed or condemned, as Fetzer and his contributors insist, it strains credulity to believe that not a single resident would have publicly questioned why children were suddenly inside the building.

More importantly, a condemned school does not exist in a bureaucratic vacuum. There would be an unmistakable paper trail—inspection failures, closure notices, board minutes, remediation plans. None exist. Instead, a publicly available school facilities survey from August 2011—years after the alleged “closure”—rates the building favorably in nearly every category, with predominantly excellent marks across the board:

This is not what a condemned structure looks like on paper. It is exactly what you’d expect from an actively used, routinely maintained elementary school.

“In 2004, the Newtown Board of Education was told “there were serious problems with the Sandy Hook elementary school roof.” pg. 30

Which is almost certainly why the district installed an entirely new roof just three years later, in 2007. As reported by the Newtown Bee on July 13, 2012:

Work on the Sandy Hook School roof began in earnest last week as materials for the $180,000 project were set in position. The project to replace the school’s entire roof won the school board’s nod over a $70,000 offer by Barrett Roofing and Supply Inc to repair leaks in the roof. The town has filed a lawsuit against Barrett for $15,000 in damages after the flat-style roof on the elementary school began leaking. The roof was installed five years ago.

This raises an obvious question Chang never bothers to ask: why would a school district spend $180,000 on a full roof replacement if it planned to abandon the building a year later? No district—especially one operating under tight budgets—throws that kind of money at a facility it intends to shutter.

This capital investment, coupled with the favorable 2011 facilities survey, demonstrates the opposite of what Chang implies. The district wasn’t preparing to close Sandy Hook Elementary; it was actively maintaining it for continued use.

“Four years later, in 2008, there was yet more bad news: SHES was contaminated with asbestos.” pg. 30

There was no asbestos “contamination” at Sandy Hook Elementary—at least not in the way Chang wants readers to imagine. What the school had was a regulated, monitored presence of asbestos-containing materials, which is common in school buildings of that era and explicitly governed by state and federal law.

The school’s own 2010–2011 handbook addresses this directly:

We have a Tools for Schools indoor environmental resource team that works in coordination with district efforts to monitor and improve air quality. Our building is inspected every 6 months as required by § 19a-333-1 through 13 of the Regulations of Connecticut State Agencies, “Asbestos-Containing Materials in Schools”; to determine any changes in the condition of identified asbestos-containing building materials. Additionally, the school will be reinspected every three years by an accredited inspector following the same basic criteria as stated in the original plan. Sandy Hook School maintains in its Main Office a complete updated copy of the asbestos management plan. It is available during normal business hours for inspection. The designated person for the Asbestos Program is Gino Faiella and can be contacted at 203-426-7615. We remind you that this notification is required by law and should not be construed to indicate the existence of any hazardous conditions in our school buildings.

This is routine compliance language, not a warning of danger. Schools across the country are required to disclose the presence of asbestos-containing materials, inspect them regularly, and document their condition—even when those materials pose no risk.

By labeling this as “contamination,” Chang is deliberately conflating lawful, monitored asbestos management with an unsafe or uninhabitable environment. The school was inspected on a fixed schedule, had a publicly available asbestos management plan, and explicitly stated that the disclosure should not be interpreted as evidence of hazardous conditions.

In other words, this wasn’t “bad news.” It was boring, bureaucratic, and completely incompatible with the claim that Sandy Hook Elementary had been closed or abandoned.

“On October 5, 2013, nearly 10 months after the massacre, a city referendum passed by over 90% in support of the demolition and rebuilding of SHES with a generous $49.25 million grant from the State of Connecticut. The reason given for the demolition was ‘asbestos abatement’.” pg. 30

Chang badly misrepresents both the referendum and the reason for demolition.

The $49.25 million grant from the State of Connecticut gave Newtown residents a choice: accept the funding to build a new Sandy Hook Elementary School—including demolishing the old structure and acquiring land for a safer access road—or reject it and forfeit the money entirely, forcing the town to independently fund schooling for hundreds of elementary students elsewhere. Unsurprisingly, the referendum passed with approximately 89% approval.

Contrary to Chang’s claim, the school was not demolished because of asbestos abatement. That assertion collapses under even minimal scrutiny. Asbestos can be—and routinely is—abated without demolishing a building. In fact, Newtown explicitly considered asbestos abatement among several options and rejected it for one simple reason: cost.

The real issue was that renovating the aging, 56-year-old building to modern standards would have been financially impractical. According to the referendum’s official Q&A:

Analysis of the renovate vs. build new by the Advisory Committee showed that costs to renovate this 56 year old building, bring it up to code, eliminate the portables, make it energy efficient, provide necessary safety features, and more, generated a cost almost at the same level of new building construction.

In other words, demolition wasn’t driven by asbestos—it was driven by economics and safety.

The asbestos removal Chang points to was simply part of the standard hazardous materials abatement process required before demolition, intended to protect workers and prevent environmental contamination. Local reporting at the time made this explicit:

Bestech will spend this weekend beginning demolition, working wing-by-wing as asbestos is removed from each section of the school, according to WTNH. First Selectman Pat Llodra told WTNH no materials from the old school building would leave the site.

“It might become part of the base for the new road or the foundation, or you know, the contractors will make the decision how best to use those materials,” she said.

Llodra told Patch abatement, which began earlier this month, is necessary before demolition can begin.

“We have to get rid of the hazardous materials on the site before we can do anything else,” she said.

This was pre-demolition environmental compliance, not evidence of an unsafe or abandoned school. Chang’s framing reverses cause and effect: asbestos wasn’t the reason the building was torn down—it was removed because the building was being torn down.

Like so many claims in this book, this one relies on readers not understanding basic construction practices or bothering to check the readily available public record.

“Classrooms and hallways were used for storage, jammed with furniture and office supplies.” pg. 32

Beginning with the second photo on the page, Chang misidentifies an image as a school hallway being used for storage. This claim collapses the moment even minimal context is restored.

Walkley’s crime scene photographs are presented in strict chronological order across 760 pages. The image Chang relies on appears on page 759—essentially the very end of the photographic record, long after forensic processing was well underway. A nearly identical image, taken at approximately the same time, appears on page 953 of 970 in Tranquillo’s Back-up Scene Photos #2, also part of the “22 Assorted Files” archive. Like Walkley’s, Tranquillo’s photos are likewise chronological.

Below is a clearer, annotated version of the Walkley photo Chang stripped of context. This image appears on page 759 of 760, placing it at the tail end of the investigation’s timeline. Click to view full-size:

In this view, odd-numbered rooms are on the left and even-numbered rooms on the right, with room numbers increasing toward the lobby. For orientation, I’ve highlighted the height markers between rooms #3 and #5, as well as the “Warm up to a good story” display between rooms #10 and #12.

A blue tarp blocks the hallway’s view into the lobby, and red biohazard bags are visible on the floor—hardly the trappings of a long-abandoned storage corridor. Several items Chang points to as “stored furniture” are identifiable elsewhere in earlier photos: the white-and-blue portable storage racks (including the one on the far right) appear inside Room #10—Victoria Soto’s first-grade classroom—on pages 161–162 of Walkley’s photos. Tranquillo’s Back-up Scene Photos #1 (pages 167 and 200) show these same racks, along with what appear to be the same desk chairs and computer workstation visible on the left.

For additional clarity, here is the same hallway marked on the Sandy Hook floor plan:

Now compare Chang’s cherry-picked image to how the hallway appeared shortly after the shooting. The following photo, from page 88 of Walkley’s scene photos, has been cropped to roughly match the perspective of the page 759 image. Walkley took this earlier photo from farther back—roughly between rooms #4 and #6—while the later photo was taken closer to the lobby, between rooms #6 and #8.

The height markers between rooms #3 and #5 are clearly visible here. I’ve circled one of Adam Lanza’s dropped magazines on the floor, and marked the approximate position from which the page 759 photo was taken. In the distance, Mary Sherlach’s body is faintly visible:

Near room #5, SWAT and EMS equipment is plainly visible: a helmet, a LifePak 15 monitor, an EMT backpack, and a bag containing mass-casualty supplies. This is not “storage”—it’s an active crime scene.

A closer view of this same area appears on page 70 of Tranquillo’s Back-up Scene Photos #1. In this image, I’ve again labeled the height markers, circled the cartridge, and indicated Walkley’s approximate shooting position. The spatial continuity is unmistakable:

At this point, the explanation should be obvious. The image Chang misrepresents was taken after investigators had begun systematically clearing rooms, temporarily staging contents in the hallway to allow unobstructed forensic access. This process is clearly documented in Walkley’s photos (pages 563–574) and Tranquillo’s Back-up Scene Photos #2 (pages 151–152), which show Room #8 almost entirely emptied. The official report (CFS 1200704597, 00118939.pdf) explicitly describes this room-by-room clearing process:

If that still isn’t enough, here is a photograph from Sandy Hook’s 2011–2012 school scrapbook, taken January 23, 2012—nearly a year before the shooting—showing this same hallway in everyday use. There are no boxes, no stacked furniture, no clutter of any kind:

The conclusion is unavoidable: Sandy Hook’s hallways were not used for storage. The only reason they appear that way in Fetzer’s book is because Chang and Fetzer deliberately presented photos stripped of chronology and context.

With nine contributors—five of them holding PhDs—you’d expect such a basic error to have been caught. Unless, of course, it wasn’t an error at all.

The same pattern applies to the allegedly “jammed” classroom pictured at the top of the page.

That image depicts Classroom #6, a special education room, taken from page 249 of Walkley’s scene photos. Chang selected the single most cluttered angle—near the teacher’s desk—while ignoring adjacent photos taken moments later that show the rest of the room. Below is a composite assembled from pages 249–251, images Chang would have had access to but chose not to show:

Not exactly “jammed.”

More damaging still is a second composite assembled from four photos taken from the opposite side of the room, just inside the doorway (pages 244–247). From this angle, the room appears even less cluttered:

As seen in both composites, there is no fire hazard here as Maria Chang claims. The path to the door is clear and unobstructed. Additionally, personal items such as jackets and water bottles are visible in both photos, further indicating an active classroom. In fact, you can even spot coffee brewing to the left in the first composite, and a December 2012 calendar is prominently visible just to the right of center. All of this points to the fact that this was indeed an active classroom and a functioning school.

There is no fire hazard here. The path to the door is clear and unobstructed. Jackets, water bottles, a coffee maker, and a December 2012 calendar are all plainly visible—hallmarks of an active classroom in a functioning school, not a storage dump masquerading as one.

Which leaves us with three possible explanations, listed here in descending order of plausibility:

- Intentional deception: Maria Hsia Chang and James Fetzer knowingly presented photos out of order and out of context to fabricate a false narrative and sell books.

- Staggering incompetence: Chang somehow misunderstood material she demonstrably had access to, and Fetzer’s editorial team failed to catch it.

- An elaborate hoax: Sandy Hook was abandoned for years, repurposed as storage, then meticulously staged—right down to seasonal decorations, personal items, fresh coffee, and deliberately misleading photo sequences—to fool the public, while simultaneously releasing the very evidence needed to expose the ruse.

Only one of these explanations survives contact with reality.

“Then there is this photo of a pile of dust underneath an alleged bullet hole in a wall outside Room 1C, which looks suspiciously like the debris from someone drilling a pretend “bullet” hole into the ceramic wall-tile.” pg. 32

It’s genuinely unclear what Chang thinks she’s proving here. Is the implication that a high-velocity rifle round striking ceramic tile wouldn’t produce dust—while a drill somehow would? Because that’s exactly backward. Ceramic tile and masonry pulverize on impact; fine particulate debris beneath a bullet strike is not suspicious, it’s expected.

What, precisely, makes this dust uniquely “drill-like”? Chang never explains. She simply asserts it, apparently hoping the reader won’t stop to think about the physics involved for more than half a second.

And if this hole was drilled, what about the dozens—if not hundreds—of other bullet holes, spall marks, and impact points documented throughout the school and meticulously photographed in the official crime scene files? Are we meant to believe those were all drilled as well? That someone methodically went room to room, wall to wall, drilling fake bullet holes and sprinkling dust beneath them for authenticity?

That would have been an extraordinarily time-consuming and unnecessary effort. Which raises an obvious question Chang never addresses: if the school was supposedly abandoned, staged, and empty, why not simply fire an actual weapon? What, exactly, would be the risk?

Once again, we’re presented with a claim that only works if the reader has no understanding of basic materials, ballistics, or common sense—and, just as importantly, no curiosity about how the rest of the evidence fits together.

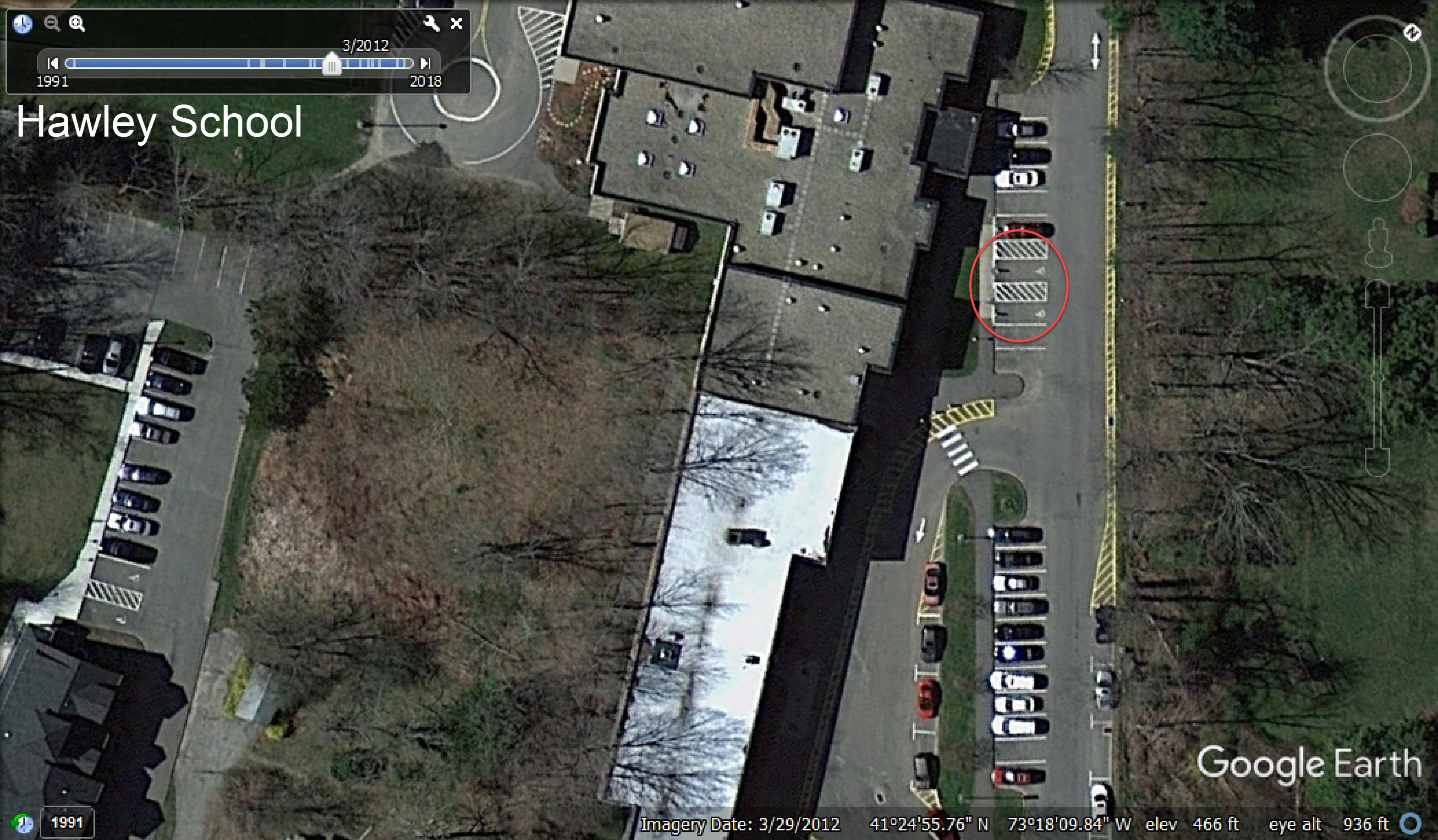

“Although the CNN image on the next page shows a wheelchair symbol painted on a parking space closest to the school’s front door, it is not painted in the now-familiar blue and white colors that have become ubiquitous certainly by 2012…

But aerial images of SHES’s parking lot, including the CNN image, show no blue-and-white signage for designated handicap parking spaces, which would make the school in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and the subsequent ADA Amendments Act of 2008 that broadened the meaning of disabilities.” pg. 32

Chang’s only source for this claim is not the ADA Standards for Accessible Design, not the Department of Justice, and not even a secondary legal commentary. It is myparkingsign.com—a retail website that sells parking signs.

That choice alone is revealing. The actual ADA standards are publicly available, easy to access, and unambiguous. They also directly contradict Chang’s assertion. Section 4.6.3 (Parking Spaces) and Section 4.30.7 (Accessible Signage) of the ADA Standards make no mention whatsoever of required paint colors for accessible parking symbols or striping. None. Blue-and-white paint is permitted, but it is not required. White paint alone is explicitly allowed.

This explains why most of Newtown’s other public schools—three elementary schools and two intermediate/middle schools—show accessible parking spaces marked in white or yellow, rather than blue-and-white, in aerial imagery from 2010–2012, with paint colors varying by site and renovation history rather than any ADA mandate:

The lone exception is Newtown High School, whose parking lot was renovated and fully restriped in 2010. Satellite images taken after that renovation show blue-and-white accessible spaces, while images taken before the renovation show those same spaces painted white—matching the pattern seen at the district’s other schools:

Are we really expected to believe that all but one of Newtown’s seven public schools—including all four elementary schools and both intermediate/middle schools—was non-compliant with the ADA in 2012 and therefore “non-operational”? And if that’s the standard being invoked, what about Chalk Hill Middle School—the building conspiracy theorists insist Sandy Hook students were secretly relocated to, despite it not even belonging to the Newtown school district? If blue-and-white paint is truly the litmus test for legality and operation, then Chalk Hill’s parking lot should be a model of ADA compliance. As the aerial photographs that follow make clear, it isn’t:

The blue-and-white paint myth has also been explicitly debunked by an ADA trainer and Information & Outreach Specialist at the New England ADA Center, who confirmed to me via email:

The ADA Standards for Accessible Design do not specify the color of the lines and markings at accessible parking spaces.

That statement alone invalidates Chang’s entire premise.

What about signage? The ADA does require a sign mounted on a post, with the bottom of the sign at least 60 inches above the ground—but only if the parking lot was built, paved, or restriped after January 26, 1992, when the ADA took effect. There is no evidence that Sandy Hook Elementary’s parking lot was paved or restriped after that date. The addition of striping to a previously unstriped fire lane between 2010 and 2012 does not qualify as restriping the parking lot, a point again clarified by the ADA specialist:

Striping a previously unstriped yet existing fire zone by itself would not be considered restriping a parking lot.

So there is no basis—legal, factual, or visual—for claiming that Sandy Hook Elementary School was out of ADA compliance in December 2012, or at any point prior.

Even more telling is what Chang’s argument would imply if it were true. Fetzer, Chang, and Halbig all acknowledge that Sandy Hook Elementary was open and operating for years before 2008. If blue-and-white paint and modern signage were mandatory without exception, then the school would have been in violation for seventeen years. What, then, is four more?

But this hypothetical collapses as well, because ADA non-compliance does not render a school inoperable. When asked directly what ADA violations actually mean in practice, the New England ADA Center explained:

An individual could file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice or the Office for Civil Rights… In a settlement, the district would agree to fix the identified issues, and there could be a fine. A school would not be closed due to the violation.

In fact, a federal investigation found that 83% of New York City elementary schools were in violation of the ADA, yet none were shut down.

So Chang’s claim fails on every level: legally, factually, procedurally, and logically. It relies on a retail website instead of governing law, ignores district-wide evidence that contradicts it, and rests on a misunderstanding of what ADA compliance even is. Far from raising legitimate questions, it demonstrates a willingness to substitute conjecture and commercial misinformation for primary sources and expert guidance.

“Arguably, the most compelling evidence that SHES had long been abandoned before the 2012 massacre is the testimony from the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine of the school’s lack of of Internet activity from the beginning of 2008 through all of 2012.” pg. 34

Maria Hsia Chang attributes this particular nugget of gibberish to either “Jungle Server” or “Jungle Surfer.” It’s unclear which, because she manages to write both. With nine contributors and multiple editors involved, one would think someone might have noticed.

But before addressing the claim itself, we need to establish a basic, non-negotiable fact: the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine does not measure “Internet activity.” Not remotely. Confusing the two betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of how the web works.

So what is the Wayback Machine?

According to its own documentation (and echoed by Wikipedia), the Wayback Machine is a digital archive that periodically crawls and snapshots publicly accessible webpages. These crawls occur irregularly—sometimes weeks apart, sometimes months apart, and sometimes years apart. Pages are only archived if the crawler happens to revisit them, or if a user manually submits them for capture. The Internet Archive is explicit about this limitation:

The frequency of snapshots is variable… sometimes there are intervals of several weeks or years between snapshots.

They reiterate this again—plainly and prominently—via a disclaimer shown directly on the calendar view for archived pages:

Let me make this absolutely clear:

A lack of Wayback Machine snapshots is not evidence of inactivity.

It is evidence of nothing whatsoever, except that no crawl occurred.

Archived snapshots are not logs. They are not analytics. They are not usage records. They are not indicators of whether a website was updated, maintained, accessed, or even existed on a live server during the gaps between captures. Treating them as such is akin to claiming a town ceased to exist because Google Street View didn’t drive through it for a few years.

By Chang’s logic, thousands of active schools, hospitals, small businesses, and municipal offices across the country would have to be considered “abandoned” simply because the Internet Archive didn’t happen to crawl their websites during a given stretch of time. That’s not skepticism—that’s technological illiteracy.

Even if Sandy Hook Elementary’s website had gone completely untouched between 2008 and 2012 (which is not the case), that would still prove nothing. Many elementary school websites—especially in the late 2000s—were static, rarely updated, or maintained at the district level rather than the individual school level. Some were little more than a contact page and a lunch menu PDF. None of that has any bearing on whether a physical school building was operational.

Conflating archival gaps with abandonment is not just wrong—it’s embarrassingly wrong. It represents a category error so severe that it would disqualify the claim in any serious academic or investigative context.

In short, this is not “arguably the most compelling evidence” of anything. It is a textbook example of how not to use digital tools, wrapped in jargon and passed off as insight.

“The Wayback Machine is a digital archive of the Internet which uses a special software to crawl and download all publicly accessible World Wide Web pages. It was Jungle Server who first discovered that the Wayback Machine shows an absence of Internet activity from SHES since 2008 — the same year when the school was found to be contaminated with asbestos.” pg. 34

There is absolutely no evidence—none—that Sandy Hook Elementary School was any more “contaminated” with asbestos in 2008 than it was in 1956, the year it was built.

For perspective: my own home wasn’t suddenly “contaminated” with asbestos when I replaced its original siding a few years ago. It already contained asbestos, because it was built in the mid-1950s, when asbestos was commonly used in construction materials. That is how time works. Buildings don’t become retroactively hazardous because someone notices what era they were built in.

Unsurprisingly, the book provides no citation whatsoever for this claim. So I tracked it down myself. The asbestos talking point originates not from any official report, but from Maria Hsia Chang’s wretched blog, Fellowship of the Minds. Chang, in turn, cites a single paragraph from a Newtown Bee article published on November 7, 2008. The original link is dead—but fittingly, the article itself is still accessible via the Wayback Machine, the very tool she so badly misunderstands.

Here is the relevant excerpt in full:

The asbestos levels in Newtown schools pose no threat to the health or safety of those using the schools, according to Superintendent John Reed. The areas in the schools where there is evidence of asbestos — the ceiling above the high school pool, areas of the upstairs floor of the Middle School A wing and the girls’ and boys’ locker rooms, are also considered acceptable and safe.

That’s it. That’s the entire basis for the claim.

If your reading comprehension is better than Chang’s—and I can only assume it is—the problem should be immediately obvious: the article explicitly states that asbestos levels posed no threat and were considered safe. It does not describe contamination. It does not describe closure. It does not even mention Sandy Hook Elementary by name. In fact, the only schools specifically identified are the high school and middle school.

So let’s ask the obvious question Chang never does:

If Sandy Hook was allegedly “contaminated” badly enough to justify abandonment, why weren’t the high school and middle school—explicitly identified as having asbestos-containing areas—closed as well?

Because they weren’t contaminated. And neither was Sandy Hook.

To put a final nail in this coffin, the Connecticut Department of Education’s 2011 school facilities survey—conducted years after the supposed 2008 “contamination”—gave Sandy Hook Elementary a 4 out of 4 (“Not a problem”) rating for Asbestos Remediation. Not “identified as a problem but issue not addressed yet.” Not “problem identified and scheduled for repair.” Not a problem.

So to recap:

Chang claims asbestos contamination → cites an article → the article says the exact opposite → and official state records flatly contradict her anyway.

This is not research. It’s laundering buzzwords through ignorance and hoping the reader won’t check.

“To verify Jungle Surfer’s claim, I searched for SHES’s website, http://newtown.k12.ct.us/~sh” pg. 34

This is where the argument fully collapses under the weight of basic technical ignorance.

Sandy Hook Elementary School had not been located at http://newtown.k12.ct.us/~sh since the summer of 2006. That URL wasn’t quietly abandoned, nor was it unique to Sandy Hook. In 2006, the Newtown Public School District’s webmaster restructured the entire district website, changing the addresses for all schools simultaneously. Sandy Hook’s URL changed again in 2011 during a second district-wide redesign.

If you enter any of those obsolete pre-2006 URLs into the Wayback Machine, you’ll see the same thing Chang mistook for evidence of abandonment: sparse snapshots, long gaps, or nothing at all.

This information is neither obscure nor difficult to verify. Yet Chang either failed to discover it or chose to ignore it, once again demonstrating why neither she nor her coauthors can be trusted to handle technical evidence—especially ironic in a book that repeatedly accuses journalists of incompetence.

Even setting aside the incorrect Sandy Hook URL, the actual Newtown Public Schools website in 2008 was http://www.newtown.k12.ct.us. Entering that address into the Wayback Machine produces a very different picture.

You’ll notice an apparent gap in snapshots—aside from a lone capture in January 2010—between November 2007 and July 2011. This gap has a mundane technical explanation, which I’ll address shortly.

Before that, look at the last snapshot before the gap, dated November 20, 2007. It clearly lists Sandy Hook Elementary School at the address: http://www.newtown.k12.ct.us/shs:

That address is independently confirmed by The Sandy Hook Connection, the school’s official newsletter, dated January 8, 2009—squarely in the middle of the period Chang claims the school had vanished from the Internet.

When you enter this correct Sandy Hook URL into the Wayback Machine, the supposed “absence of Internet activity” shrinks dramatically—from four years down to a gap running roughly April 2008 to October 2010.

So let’s pause here. Are we really meant to believe Sandy Hook Elementary School closed in April, with barely two months left in the academic year?

Of course not.

So what explains even this shorter gap? The answer is documented, banal, and fatal to Chang’s argument.

According to the Wayback Machine’s own FAQ, websites can prevent archiving by using a simple file called robots.txt, which tells web crawlers what they are not allowed to index. From the Internet Archive:

How can I have my site’s pages excluded from the Wayback Machine?

You can exclude your site from display in the Wayback Machine by placing a robots.txt file on your web server that is set to disallow User-Agent: ia_archiver. You can also send an email request for us to review to info@archive.org with the URL (web address) in the text of your message.

And that is exactly what happened.

On June 4, 2008, the Newtown Public Schools webmaster added the following lines to the district’s robots.txt file:

"User-agent: *"applies to all web crawlers."Disallow: /"tells the crawlers not to visit or archive any pages on the site.

Translated into plain English: all web crawlers are forbidden from archiving any page on this site.

Once that file was added, the Wayback Machine—by design—stopped archiving every school in the Newtown district, not just Sandy Hook. This wasn’t selective. It wasn’t secret. And it certainly wasn’t evidence of abandonment.

Anyone can replicate this process in minutes. I encourage readers to do so—unlike the contributors to this book, who apparently never tried.

If this is Maria Hsia Chang’s “most compelling evidence” that Sandy Hook Elementary closed in 2008 to prepare for an imaginary hoax, it speaks volumes about the quality of the rest of her claims.

Still, a few diehards remain unconvinced. Self-described IT professional Ruth Teltru writes:

Still very suspicious that it just so happens Sandy Hook Elementary is the only school in CT. that had the internet archive issues.

This statement is false on multiple levels.

First, as already shown, the robots.txt file applied at the district root, affecting every Newtown school equally—not just Sandy Hook.

Second, even if we charitably substitute “Newtown Public Schools” for “Sandy Hook Elementary,” the claim remains demonstrably wrong. I checked the Wayback Machine records for every school district in Connecticut.

Nineteen districts had archive gaps longer than Newtown’s. Three had gaps exceeding four years.

Those screenshots aren’t an anomaly; they’re the rule. Once you bother to look beyond Sandy Hook—and unlike Ruth, actually check—the myth of Wayback Machine gaps as evidence of school closures collapses immediately. Newtown wasn’t unique. It wasn’t even unusual. Large archival gaps appear across school districts in Connecticut and nationwide, for reasons that are well understood, well documented, and entirely mundane.

But rather than stop there, let’s take this argument where it should go—by applying the exact same standard to one of the loudest and most persistent voices promoting it.

If Wayback Machine gaps are truly proof that a school has been abandoned, then we are obligated to follow that logic wherever it leads—even when it leads straight back to Wolfgang Halbig.

Halbig—who has spent years harassing victims’ families, filing frivolous records requests, and promoting the claim that Sandy Hook Elementary was secretly closed—lists on his own résumé that he worked at Lake Mary High School and Lyman High School in Seminole County, Florida. By the logic Chang and her fellow conspiracists insist upon, these schools should now be subjected to the same suspicion they gleefully direct at Sandy Hook.

Let’s start with Lake Mary High School.

Its website (lakemaryhs.scps.k12.fl.us) shows not one but two massive gaps in Wayback Machine coverage. The first runs from April 2003 to December 2005—over two and a half years of alleged “Internet inactivity.” The second gap is even more damning by Chang’s standards, stretching from February 2009 to July 2011, save for a single, lonely snapshot in 2010. By denialist logic, Lake Mary High School must have been closed, abandoned, or secretly repurposed—perhaps as a warehouse or FEMA staging ground.

Now let’s look at Lyman High School.

Its Wayback record is nearly identical. Long, uninterrupted gaps. Missing years. Sparse captures. Exactly the sort of “evidence” that Chang insists proves Sandy Hook Elementary had been shuttered since 2008.

So which is it?

Were both Lake Mary and Lyman High Schools quietly closed for years? Were students secretly relocated? Or—far more plausibly—do Wayback Machine gaps mean absolutely nothing about whether a school is operational?

This is where the irony becomes inescapable.

Halbig has spent the better part of a decade accusing grieving parents and murdered children of being fictional, while the very schools on his own résumé exhibit the same or worse archival gaps he claims are proof of a hoax. By his own standards, Halbig’s professional history becomes evidence against him.

And it gets better.

Halbig has publicly admitted to mold issues in schools he managed—another favorite trope among Sandy Hook denialists. So if we follow this reasoning to its logical conclusion, perhaps Lake Mary and Lyman High Schools were also “contaminated,” secretly abandoned, and transformed into storage facilities. Perhaps they were being prepped for future false flag operations. Perhaps Halbig himself knows more than he’s letting on.

Or—and this is the part denialists never seem willing to confront—their entire argument collapses the moment it’s applied consistently.

Wayback Machine gaps are common. They are mundane. They are technical artifacts—not evidence of conspiracies, abandoned schools, or staged massacres. And when the same standard is turned on one of the movement’s loudest figures, it doesn’t just fail—it boomerangs.

If Wayback Machine gaps prove Sandy Hook Elementary was closed, then Wolfgang Halbig’s own career becomes Exhibit A in an even larger conspiracy. And if that sounds ridiculous, it’s because it is.

Which is precisely why this argument was never made in good faith to begin with.

Additional reading: “When The Internet Archive Forgets”

Next: Chapter Three: “Wolfgang Halbig Goes For The Jugular In His FOIA Hearing” by James Fetzer

Comment policy: Comments from previously unapproved guests will remain in moderation until I manually approve them. Honest questions and reasonable comments from all types of folks are allowed and encouraged but will sometimes remain in moderation until I can properly reply to them, which may occasionally take a little while. Contrary to what some of you think, losing your patience during this time and leaving another comment in which you insult me won't do much to speed up that process. If you don't like it, go somewhere else.

The types of comments that will no longer be approved include the following:

1) Off-topic comments. An entry about The Internet Archive's Wayback Machine are not the place to ask about Hillary's e-mails or pizza shop sex dungeons. Stay on topic.

2) Gish Gallops. Don't know what a Gish Gallop is? Educate yourself. And then don't engage in them. They are an infuriating waste of everyone's time and there is no faster way to have your comment deleted.

3) Yearbook requests. Like I told the fifty other folks asking for them: I don't have them, and even if I did, I wouldn't post them. I'm not about to turn my site into some sort of eBay for weirdos, so just stop asking.

4) Requests for photos of dead children. See above. And then seek professional help, because you're fucked up. These items are unavailable to the public; exempt from FOIA requests; and in violation of Amendment 14 of the US Constitution, Article 1 Section 8b of the Connecticut State Constriction, and Connecticut Public Act # 13-311.

5) Asking questions that have already been answered/making claims that have already been debunked. If you want to have a discussion, don't make it painfully obvious that you haven't bothered to read the site by asking a question that I've already spent a significant amount of time answering. I'll allow a little leeway here if you're otherwise well-behaved, but please, read the site. There's a search function and it works fairly well.